“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

– George Santayana, The Life of Reason, Volume 1

In America, the summer is bookended and filled with many of our traditional “patriotic” holidays (if you don’t like Labor Day as patriotic then shift it back a week or two and you can choose Patriots Day (Sept. 11th) or Constitution Day (Sept. 17th) – just not as great sales on mattresses for those two). This all begins the last weekend of May with Memorial Day.

Memorial Day is an interesting holiday. Originally called “Decoration Day” and celebrated to honor soldiers who had died in the Civil War, the last Monday of May is officially set aside to commemorate those who have died serving the United States. Every year you have likely seen people sharing reminders that the weekend is not about grilling and pools, and more recently there has also been a more visible push to remind people that thanking active duty military for their service is great, but for this particular day that kind of misses the point.

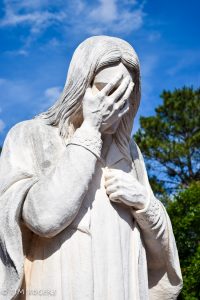

Outside of specific days, we also try to remember sacrifices, events, and individuals with monuments, memorials, plaques, statues, benches, and more. One of the most interesting things about living in the Washington DC area (especially as a history nerd) was that there were monuments and memorials just about everywhere, and they could easily fill you with just about every possible emotion and feeling. While not quite as widespread, these sorts of tributes can be found across the country.

This year over the Memorial Day Weekend, I was able to visit the Oklahoma City National Memorial for the first time.

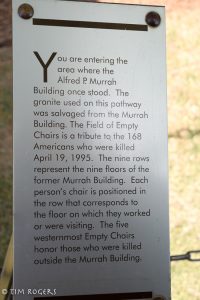

On April 19, 1995, at 9:02 am the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City was bombed by Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols. 168 people were killed, hundreds more were injured.

The memorial stands on the site of the former federal building. When coming towards it, one of the first things you see is a chain link fence. This fence was initially erected around the remains of the attack, but quickly became a place where people would leave remembrances. This became an official part of the memorial site, and all items are collected and archived.

The museum holds over 60,000 of these items.The most striking feature are the “Gates of Time,” which also serve as the entrances to the outdoor symbolic monument. As described by the memorial, 9:01 describes the innocence of the city before the attack. 9:03 represents “the moment we were changed forever, and the hope that came from the horror in the moments and days following the bombing.”

Outside of the gates, the memorial has several distinct areas with their own unique purposes. The center is a reflecting pool, which used to be a street, that is meant to provide a peaceful and thoughtful setting.

Survivors are acknowledged, both with a wall and a tree. This particular tree, known as “The Survivor Tree” withstood the explosion of the attack and was kept a part of the memorial to symbolize resilience. The Rescuers’ Orchard surrounds the Survivor Tree with nut and fruit bearing trees.

In the footprint of the Murrah building stand 168 chairs that represent the lives lost in the attack, with locations aligned to their location in the building. The smaller chairs signify the 19 children who were killed.

At the beginning of this post I quoted George Santayana about the consequences of not remembering. I fear we are well along that path. On Memorial Day, we wave an American flag and thank a troop for their service, and then head back to the grill without thinking of the numerous wars, conflicts, and dangerous situations to which we have troops deployed, almost entirely without discussion, let alone debate or authorization in congress.

At the beginning of this post I quoted George Santayana about the consequences of not remembering. I fear we are well along that path. On Memorial Day, we wave an American flag and thank a troop for their service, and then head back to the grill without thinking of the numerous wars, conflicts, and dangerous situations to which we have troops deployed, almost entirely without discussion, let alone debate or authorization in congress.

At the same time, the same anti-government sentiments that motivated Timothy McVeigh have only grown. We saw a spike in the number of these types of groups during the Obama presidency, and definitive action against the government, such as the armed occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon. The rhetoric against the government, even sometimes by people serving in it, has ramped up considerably over the past few years, especially in places in the U.S. that are a lot like Oklahoma.

All of this makes me wonder – what really is the purpose of memorials like this? Are we supposed to simply feel a little sad and not actually learn anything from our own history? Or is it just easier to not think about the horror that comes from those that might look or sound more familiar to us.

When Inglorious Basterds came out, I heard an interview with Quentin Tarantio about the use of language in the film, and one point he made was that World War 2 was the last American war against white people, and as such where most of the combatants all looked about the same. The point here was about how using multiple language could allow intricate spying situations, but also brings up our most recent conflicts, where we associate a certain “difference” as the enemy. It is much easier for us as a culture to think that all attacks come from people who look, sound, and worship a certain way that we can mentally categorize as “different” from “us.” To not even get into the self-destructiveness of this sort of alienating strategy, the specificity of thinking that only one type of person is the “enemy” also causes us to ignore equally or more dangerous threats from within.

A recent study pointed out how much more coverage incidents presumably perpetrated by Muslims have versus those perpetrated by non-Muslims. All of this ends up in a feedback loop, but we are capable of stopping it. We can address dangerous extremism from white nationalists wanting to start a race war, home grown lone wolf attackers who are adopted by terror groups, and all kinds of other atrocities without doing so in an inflammatory and discriminatory manner that only serves to reinforce the worst instincts of both sides.

The challenge is to take the memorializing we do and use it for common good. Addressing extremism, even if it comes from familiar faces. Centralizing the sacrifices of our military to all of society and making real the implications of our decisions. Taking extra time to address specific problems and incidents without dividing us further. But the crucial step is to actually learn and grow. This is summed up by Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan:

“We can learn from history, but we can also deceive ourselves when we selectively take evidence from the past to justify what we have already made up our minds to do.”

Each of us is able to do this, we just need to follow the mission statement adopted by the Oklahoma City Memorial: “We come here to remember those who were killed, those who survived and those changed forever. May all who leave here know the impact of violence. May this memorial offer comfort, strength, peace, hope and serenity.” The challenge is to do all of this, to remember, to learn, and to find peace.